The Olympus Pen half-frame camera: Keeping it simple!

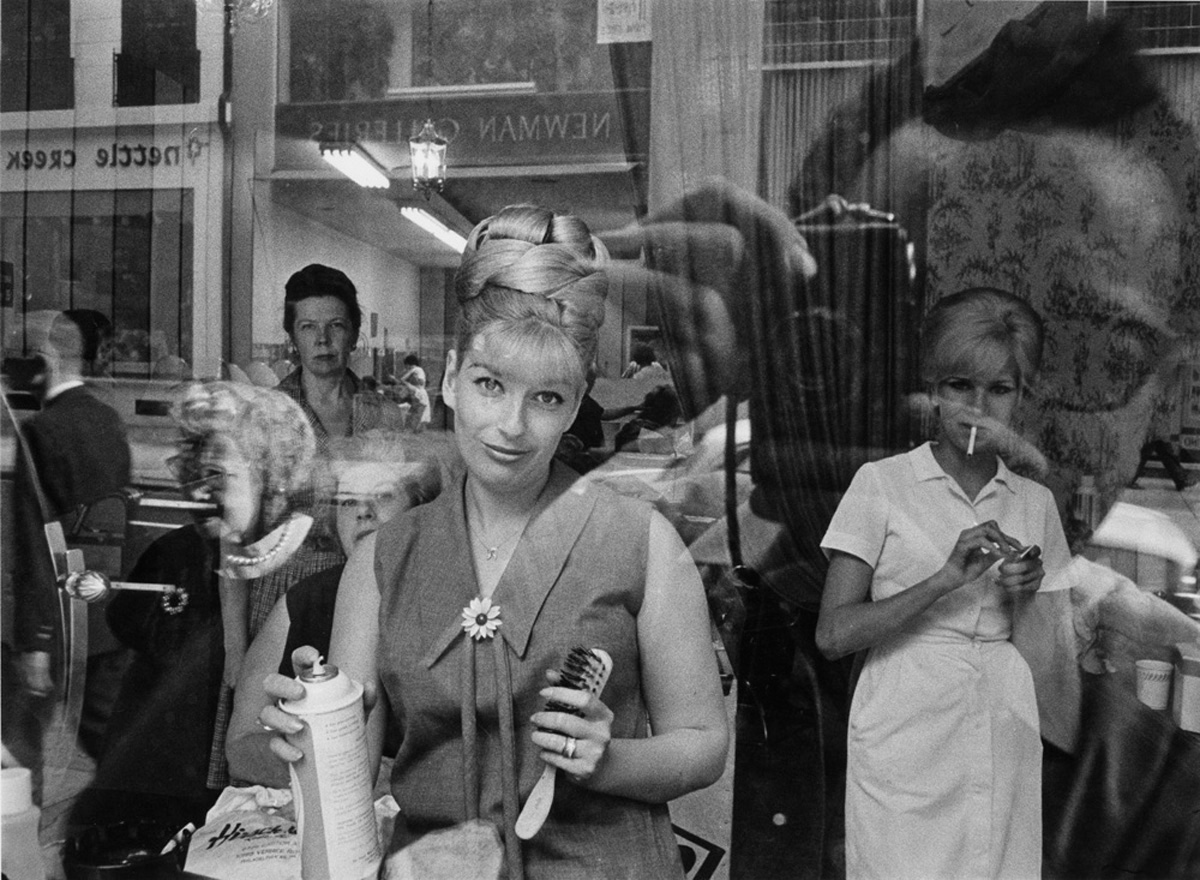

At my Aperture event recently a former student asked whether or not my new book contained any photographs taken with the Olympus Pen half frame camera I used during the mid-60’s. The answer is yes. It was a camera I loved using. Interestingly, the photo above, Beauty Parlor Window (1964), appeared on Mike Johnston’s excellent blog Online Photographer during the Kickstarter campaign in 2011 and generated a guessing game about what camera I was using that would be held vertically and produce a horizontal image. Soon enough one of the blog readers guessed correctly.

I have used and loved many cameras in my 65 years of photographing and this was one of my favorites. The reasons are simple: it was compact, easy, had great depth of field and 72 frames to a roll — meaning, cheap! Since I bought my film in 100 foot rolls and loaded it myself, it was even cheaper! As a half-frame camera, the orientation for holding the camera produces the opposite format photograph (e.g. hold the camera vertical to get a horizontal photo and vice versa).

Olympus made a number of versions of the Pen camera (so named because it aspired to be small like a pen!) The one I owned was the Pen W. The depth of field of its 25mm lens meant that when I went out to shoot street photography, I would set it for 8 feet and everything from 3-20 feet was in focus which was a great advantage. (This nifty webpage shares more info about the various iterations).

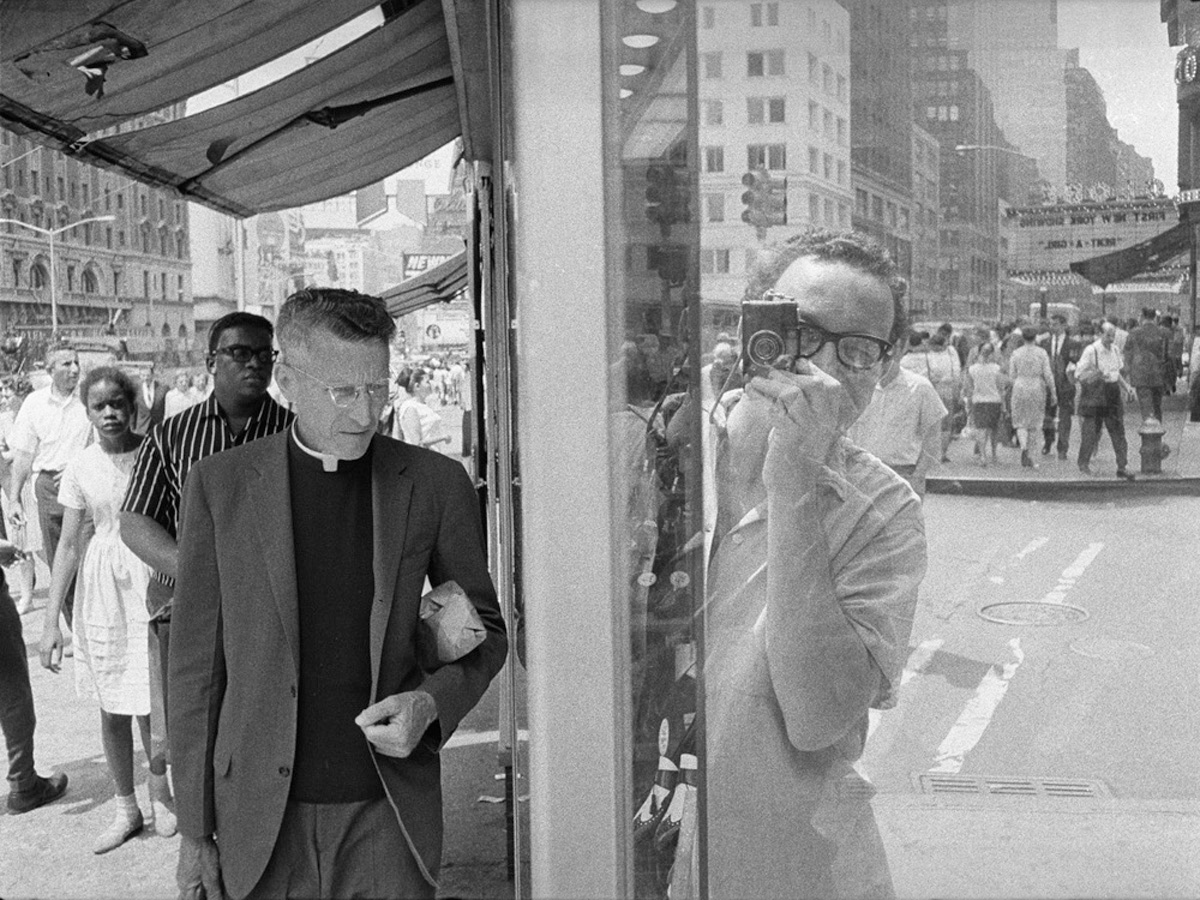

I thank Gene Smith for turning me on to this camera. Sam Stephenson, author of the wonderful book The Jazz Loft Project posted this short contribution from another of my students, Irving Goldworm, who remembers my stories about Gene’s affinity to the camera and how he easily convinced me to get one.

Photographer Irving Goldworm checked in over the weekend with the following memory, courtesy of his 1963 photography course with Harold Feinstein, who of course was an old friend and longtime associate of Smith (and an invaluable resource to me). Irving said:

Once Smith was touting to Harold Feinstein the virtues of the forty-five dollar Olympus half-frame camera he had bought. He explained: “It has a very sharp lens; there’s no camera nonsense about it; no accessories or interchangeable lenses; people aren’t intimidated by a guy carrying so unimposing a gadget; and, oh yes, you can’t pawn it.”

HERE is an interesting 2009 piece from The Online Photographer about the half-frame camera and it includes a vintage advertisement for it featuring one WES.

Thank you, Irving.

Some years ago some folks from Nikon came up to our house to interview me about my work. In the process they asked me about what cameras I like the best. Without mentioning brand names I said I like easy. I’ve never been one for bells and whistles, preferring instead something that fits nicely into my hands (small) and makes taking pictures simple. (Those who know me well know that “easy” and “simple” at least partially define my philosophy on photography!) Truth is, after my love affair with the Pen, I stayed with Olympus, among others, and still have the OM-4, which I’ve used for over three decades now. It, too, is small and easy.

I never knew about Yoshihisa Maitani who designed the Pen camera for Olympus when he was a young and junior level engineer. He details his story and the story of the Pen in this truly fascinating talk, which may be of particular interest to camera history buffs. After coming out with the first Pen, which the Olympus factory manager refused to produce (resulting in having it sub-contracted to a different manufacturer), Maitani wanted to make an even simpler model. He explains it this way:

In those days, almost all camera buyers were men: men accounted for about 98% of the market, and women around 2%. Men like machines. They dream of Harley-Davidsons. That’s why we made cameras with so many controls. The accepted wisdom was that real cameras had to have lots of controls.

He goes on to talk about wanting to make a camera for women. Obviously he’s in need of a bit of re-education here about women liking simple and men liking complicated! Suffice it to say that I require something simple! But here’s the point. He wants to make an easy camera and comes up with resistance. The camera, he was told, wouldn’t be a “proper camera.”

This concept was the exact opposite of the cameras that were selling well on the market. The sales staff told me that it wouldn’t be a proper camera, and I later heard that a conference of branch managers had also concluded that my design would not be a real camera. The head of the sales division came to see me in person and tried to persuade me to abandon the idea. I’d only been with Olympus for about three years, and it was only a year since I’d returned to the design department after my training in the factory. I was just a youngster. And yet this executive came to see me. He sat down with me and begged me to give up my idea.

I realized that the barrier of accepted wisdom was about to prevent my idea from becoming reality, so I asked him to wait until the next day, when the prototype would be ready. I worked all through that night, and the next day I showed him the camera. He played with it in silence for about 30 minutes. Finally he looked at me and said, “Maitani, let’s do it!” As the proverb says, a wise man will change his opinion, a fool never.

Maitani’s wisdom prevailed and over 17 million of these cameras sold. I like this guy and feel like he designed this camera with me in mind. Inspired by his thoughts, I would add — “Always question accepted wisdom”. How else will you ever do something original? And, oh yeah, don’t forget to keep it simple! Thanks to Maitani’s great camera, I was able to do just that.

Great article! Love the history…

My Mom Edna Bullock loved her Olympus Pen F and used it to create a marvelous series of Flea Market images. She also liked small, simple, and easy with a capacity for many exposures. It was the perfect camera for this project where she was often in crowded situations with lots going on.

Barbara: I wish I had known your mother. Obviously we had a lot in common! Thanks for carrying on her legacy and letting me know about her life and work!

I’m the (former) student who asked the question. Studying with Harold led me to get my O-P W. The camera came apart into two unhinged pieces (much like my Leica M-2) for loading film. Consequently it was possible for me to drop either half without harming the other, something I did on several occasions. Back then the factory would replace whatever part I’d destroyed. It was said that Abe Lincoln only had one hatchet, but that it went through two heads and 3 handles. My Olympus-Pen W had a similar life.

Richard: So glad you came to my event at Aperture. And..thanks for posing the question that got me thinking about the Olympus Pen again. For the past some years I haven’t been able to move around so well and have ended up doing a lot of my work in the studio. Started using the scanner as a camera. Haven’t dropped it yet!

Harold: You inspired me to dust off my camera, and start looking through the lens. In fact, it has become an appendage through which I see the delicate grace of life in all its beauty everywhere. Perhaps one day I shall be fortunate enough to attend your workshop.

Cheers and best wishes!

Thank you for your comments here! I do hope that the time comes when I can see you again and you do take one of my workshops. But I must warn you that I’m 82 this year and there may only be another 40 years left when this is possible!

Great article. I mostly use compact cameras for street photography and recently bought an Olympus Pen S to use for a new body of work in Philadelphia and New York City. I’m hoping it becomes reliable after it gets CLA’d. I would love to pick up another “S” or “W”.

Dear mister Feinstein, What a pleasure seeing the pictures of, and reading this article. I am 29, dutch, and live in Amsterdam. I recently stumbled upon an Olympus Pen EF, while cleaning up my mom’s house. It is the first camera I ever used, and recently I made my first pictures. All better in their enthusiasm then their quality! But that doesn’t matter, yet. It is lovely to just learning through this proces of trail and error, and the surprise of not knowing yet what your picture will end up looking like. In this day-and-age of ‘instant’, I really like… Read more »

[…] and here is another person who likes Olympus […]

I have been using this camera in my first year of university. I have fallen in love with it! thank you for being inspiration for my work!